|

<NOTE>

Published online (November 16, 2020)

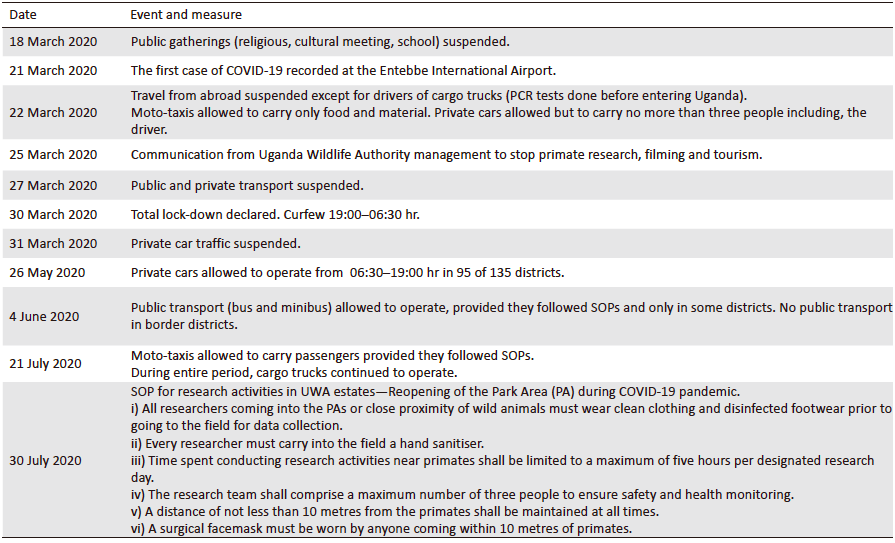

COVID-19 and chimpanzees from a field perspective: Mitigation measures, ecological and economical situation after four months in Sebitoli, Kibale National Park, Uganda

Sabrina Krief 1,2

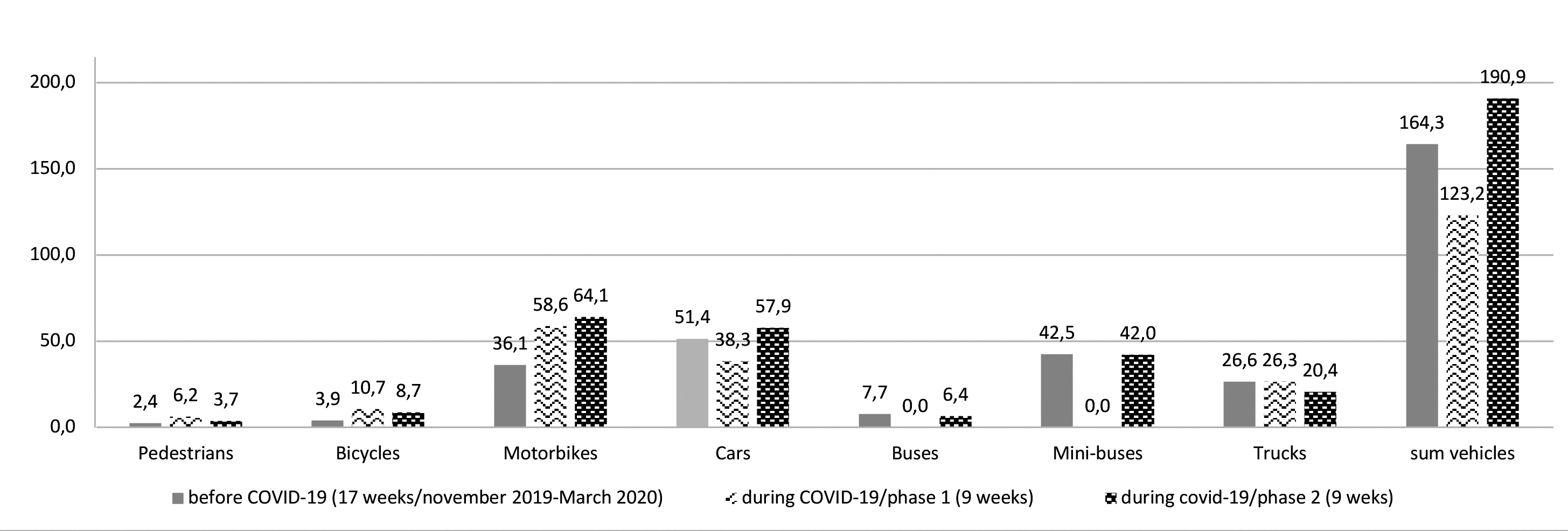

Edward Asalu 5 & Jean-Michel Krief 2, 1 UMR 7206 CNRS/MNHN/P7, Eco-anthropologie, Hommes et Environnements, Muséum national d´Histoire naturelle, Musée de l´Homme, 17 place du Trocadéro, 75016 Paris, France 2 Great Ape Conservation Project (GACP), Sebitoli Research Station, Kibale National Park, Fort Portal, Uganda 3 Fondation Nicolas Hulot pour la Nature et l´Homme, 6 rue de l´Est, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France 4 Kinomé, Campus du Jardin d´Agronomie Tropicale de la ville de Paris, 45 bis avenue de la Belle Gabrielle, 94736 Nogent sur Marne cedex, France 5 Uganda Wildlife Authority, Uganda INTRODUCTION The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak has led to the confinement of about two-thirds of the world's population (Bates et al. 2020). The emergence of the virus seems to be related to the increase in the interaction between wild animals and humans. Two main drivers have been proposed to explain it (1) the encroachment of human activities into wild areas and forests, and (2) the (legal and illegal) expanding international market of bushmeat and live wild animals from tropical and sub-tropical areas for food and traditional medicine, sold in unsanitary conditions (Volpato et al. 2020). While the biology underlying susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection remains to be fully elucidated, it is now well-established that the virus infects the endothelial cells in targeting the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor. Apes exhibit the same set of amino-acid residues in ACE2 as humans, making them highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 (Melin et al. 2020). With the restriction of national and international traffic to limit the virus transmission, many benefits were expected for wildlife from this "anthropause," as a consequence of reduced habitat disturbance (Rutz et al. 2020). However, the reverse also has been noticed in some places, with an increase in poaching and illegal activities (Rutz et al. 2020). Besides the dramatic consequences on human health of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), this unique case of global reduction of human mobility and activities may be viewed as an opportunity to better estimate both positive and negative effects of human impact in different ecosystems and on different species (Bates et al. 2020). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Sebitoli chimpanzees living in the north of Kibale National Park (Uganda) experienced a high level of pressure from human activities, such as intensive agriculture, road traffic and related pollution (Cibot et al. 2015; Bortolamiol et al. 2016; Krief et al. 2014; 2017; 2020; Spirhanzlova et al. 2019). They also were indirect victims of wire snares set by poachers to catch duikers for bushmeat (Cibot et al. 2016). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Sebitoli Chimpanzee Project (SCP) monitored the direct and indirect consequences of COVID-19 in terms of health, environment and the economy in order to mitigate them. Based on our preliminary results, we propose perspectives for researchers and conservationists on possible tools and measures to protect great apes and their habitats in the contexts of such pandemics. STUDY SITE The home range of the Sebitoli Chimpanzee community covers 25 km2 in the far north of the Kibale National Park, Uganda (795 km2; 0°13′ to 0°41′N and 0°19′ to 30°32′E). Since 2008, SCP has monitored daily this community of about 80 chimpanzees. In 2020, before the pandemic, SCP consisted of 25 Ugandan field assistants working to: collect scientific data, conduct anti-poaching operations, implement education and community-based programmes, and maintain the trail systems, managed by one of us, JPO, coordinator. During the lockdown decided by the Ugandan government and Uganda Wildlife Authority, eight of the assistants were confined in the National Park, i.e. they did not have contact with the population outside of the research station. Food was ordered and delivered at the gate of the station and communication between France (direction of the project) and Ugandan team was maintained daily with social networks and weekly with visioconferences. METHODS We adapted the usual protocols to record chimpanzee behaviour and health and to reduce threats of poaching in accordance with Uganda Wildlife Authority guidelines. We set up 14 camera traps at the most commonly-visited locations (feeding trees and crop-fields) and memory cards were collected twice weekly for immediate reading. We designed new datasheets: identity of chimpanzees and when possible, general condition, injuries, respiratory function (sneezing, coughing), locomotion, appetite, faecal consistency, reproductive status of females were scored. We collected data on illegal activities during antipoaching patrols five days per week. Two teams were dedicated to this task during the COVID-19 period, wereas usually only one was active. We counted twice weekly, the number of vehicles travelling in both directions along the road inside the protected area. On 19 May and 27 July, 2020, we collected all plastic bottles and other litter discarded by people from the vehicles along the 4.6 km of roadsides (4 m each side of the tarmac within the national park). RESULTS Protecting Sebitoli chimps and local communities : sensitization by SCP From 21 April through July 2020, a series of measures were adopted by the government and Uganda Wildlife Authority, modulating the level of human activities in and around Kibale National Park (Table 1). Although SCP, even before the pandemic, had implemented preventive measures against transmission of human respiratory diseases to chimpanzees (e.g. keeping distance between observers and apes, wearing surgical masks, using sanitizer, not spitting in the forest...), to reduce an emergent risk of the new coronavirus transmission, SCP initiated communication related to safety recommendations. The SCP team designed posters using pictograms to highlight the risks and the measures to reduce them (Figure 1). The targeted public was: (1) SCP field assistants at the research station and in the forest when authorized to carry out health monitoring, anti-poaching patrols, and transect maintenance in the National Park; (2) villagers, especially those who neither know how to read nor speak English, thus the simplicity and pictorial nature of the messages. Table 1. Confinement measures and Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) taken in Uganda

*click image to enlarge

*click image to enlarge

Figure 1. Posters designed to sensitize SCP staff and local farmers to COVID-19

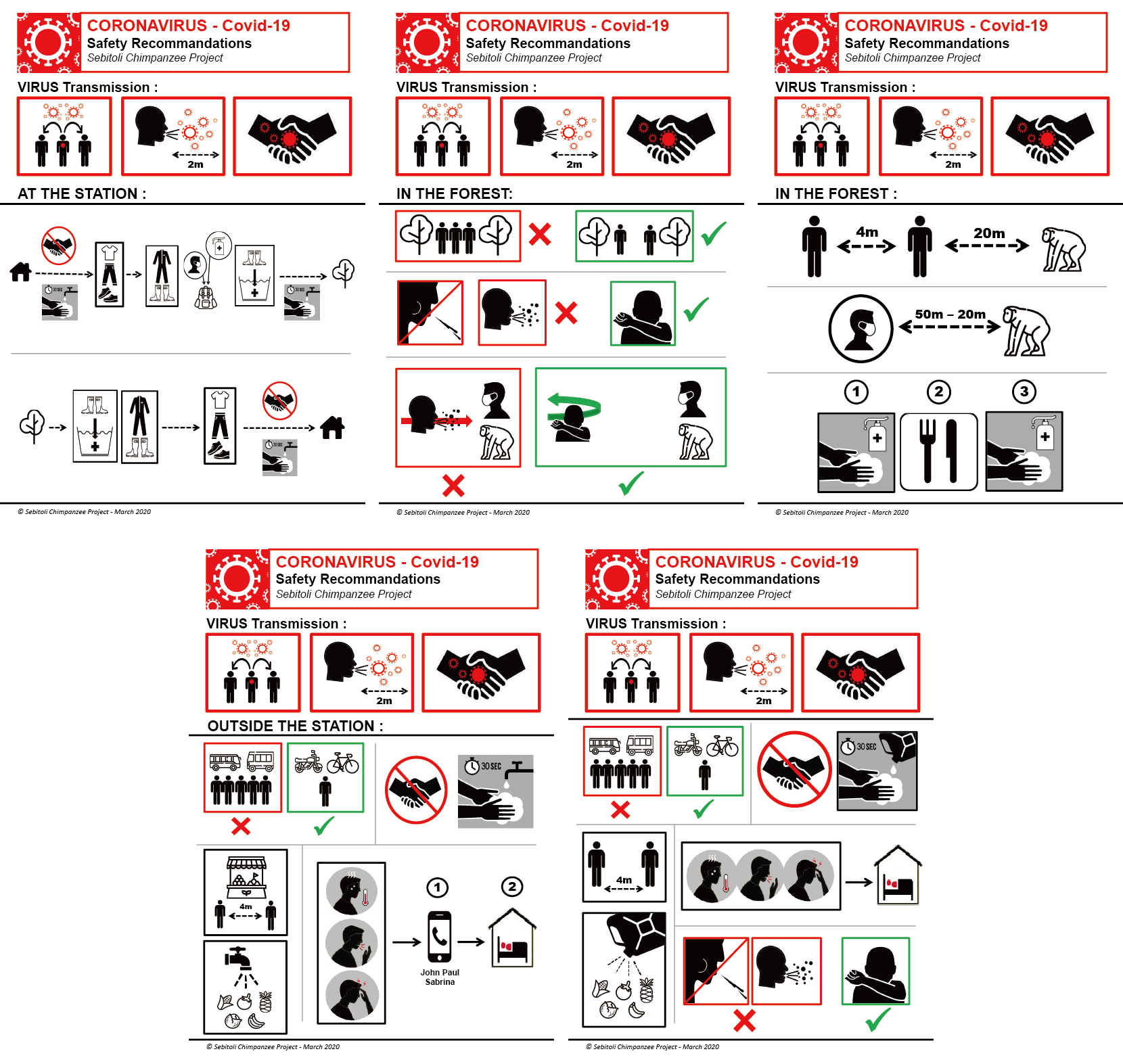

Indirect monitoring of the chimpanzees using camera traps Over the first eight weeks, 51 chimpanzees were seen a total of 612 times. None was diagnosed as showing severe symptoms (sneezing, coughing, apathy), which can indicate COVID-19. Injuries were observed (see below, poaching section). Economic situation during the four months of COVID-19 confinement We made very basic estimates of the economic consequences for local communities, using as a proxy of the cost of living, the price of common foods. Over eight weeks after the traffic was suspended (15 May, 2020), all food-item prices had increased (Figure 2).

*click image to enlarge

Figure 2. Cost of some basic food items eaten locally around the study area before the COVID-19 period and during the COVID-19 period. Prices are given in Uganda shillings for 1 kg of food except for posho (maize flour, 10 kg).

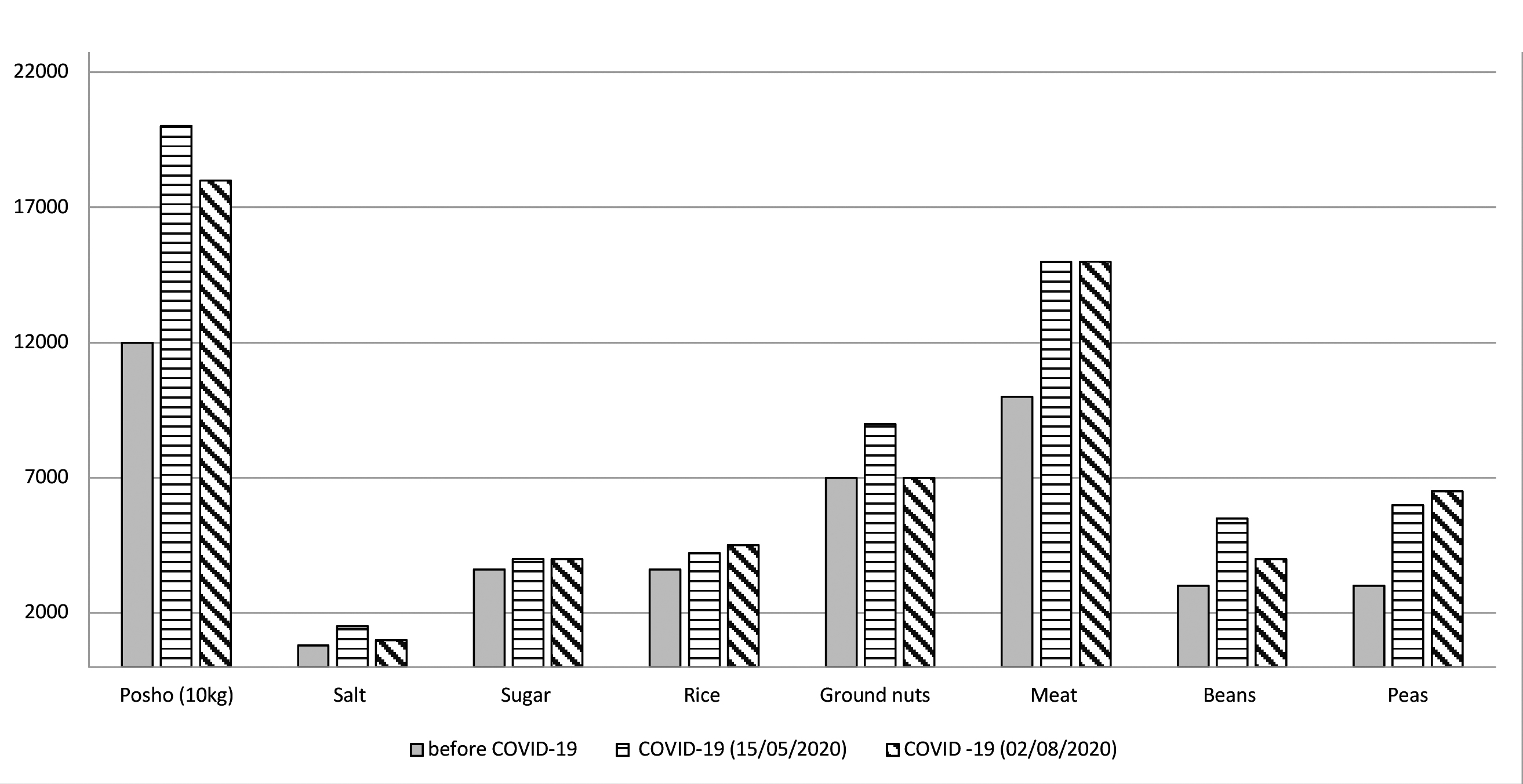

Ecological situation during the four months of COVID-19 confinement Public transport (by bus, minibus) was almost absent between 25 March and 4 June, i.e. over more than two months (Figure 3).

*click image to enlarge

Figure 3. Traffic (mean number of pedestrians and vehicles/hour) on the tarmac road from Fort Portal to Kampala before and during the COVID-19 period.

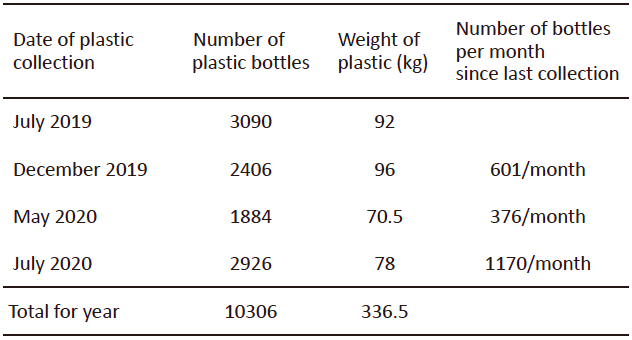

Despite this substantial reduction of traffic, - A subadult female chimpanzee, CP (Chapati) estimated age of 14 year, was knocked dead by a vehicle on the tarmac road on 8 May, 2020 (Figure 4). Since 2012, three Sebitoli chimpanzees were killed on this portion of road (Krief et al. 2020). - On 27 July, 2020 : 2626 bottles (52 kg) and 26 kg of other plastic waste were collected with the assistance of the Uganda Wildlife Authority. Seventy-eight kg of such litter had accumulated in only 10 weeks (19 May to 27 July, 2020) since the last collection during the confinement. Twice as many bottles were collected during the COVID-19 period (1170/month) compared to a mean number of 601 bottles/month in the four months, at the end of 2019 (Table 2; Figure 5).

Table 2. Plastic collection along the Fort Portal-Kampala road, in the section crossing Kibale National Park and the home-range of Sebitoli chimpanzees.

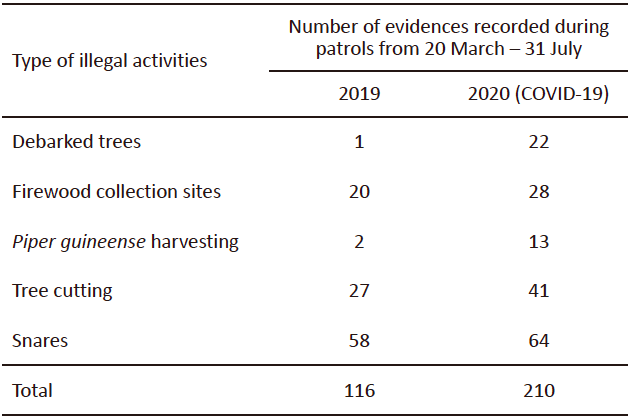

The total number of snares recovered was similar during a four-month period (25 March to 31 July) in 2019 and 2020. Patrols found a mean number of 0.70 snare/day during the COVID-19 period (64 in 91 working days) against 0.85/day in 2019 during the same period (58 in 68 working days). However, other illegal activities related to flora increased by a factor of 2.5 in 2020, especially those that generate income, such as Piper guineense (13 cases vs 2) and tree cutting for getting bark from medicinal trees (such as Prunus africana) (22 vs 1) (Table 3). Also, several observations indicated an increase of illegal activities, including poaching: One of the camera traps was stolen on 7 May, 2020, and the presence of dogs attacking chimpanzees in the forest was also observed in camera-traps and reported to the Uganda Wildlife Authority (two dogs observed in four occasions). Table 3. Illegal activities recorded during patrols of Sebitoli Chimpanzee Project in chimpanzee home-range from 25 March – 31 July in 2019 and in 2020 (since confinement was declared in Uganda).

We also observed three cases of severe injuries to chimpanzees caused by poaching over the COVID-19 period, while no case had been observed in 2019: Subadult male GR (17 April, 2020) had a large wound (at least 4 cm) on his left thigh, attributed to a spear; Infant female, dependant of FR (27 May, 2020) had a severe injury on her right foot from a snare; Subadult male LK (14 July, 2020) had a severe injury on his left hand from a snare (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION In the Sebitoli area, a strict sanitary protocol was applied for the field team confined in the protected area. The direct effects of COVID-19 on the chimpanzees' health, as monitored by camera traps, did not reveal respiratory symptoms. Camera traps enabled us to discover severe injuries caused by poaching (wires and spear) on Sebitoli chimpanzees. While the number of snares recovered by the anti-poaching patrols did not increase compared to the same period in 2019, damages to the habitat have more than doubled likely due of loss of revenues in local communities. Despite the fact that public transport was banned, no detectable positive consequences were noted along the road inside the park, with a female chimpanzee being knocked dead and the number of plastic bottles along the road having more than doubled compared to the period before the lockdown. Unfortunately, the relaxation of the pressure expected on wildlife did not occur and the indirect effects of COVID-19 on wild chimpanzees and their habitat in Sebitoli area seems more negative than positive, in general. This case study in a small part of a protected area emphasized: (1) the relevance of camera-traps' use to reduce proximity with apes in such circumstances, and (2) the importance of strengthening efforts to contain illegal activities. We suggest that sharing local experiences with other study-sites, harmonizing protocols, and increasing indirect monitoring of apes' habitat (e.g. drone, camera trap) are necessary to be ready to react to future emerging disease outbreaks. The potential cascading impacts of COVID-19 from international travel restriction, reduced tourism, local food insecurity, poverty increase, and funding reduction due to global economic shrinkage show the importance of supporting local agencies and civil society. This point is proposed to IUCN World Congress 2021 in the motion 115 – "Strengthening great ape conservation across countries, in and outside of protected areas, involving local actors" and shall be also considered to diversify revenue-operating actions from wildlife areas (Lindsey et al. 2020). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank the Uganda Wildlife Authority and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology for authorizing our research in the Kibale National Park. We are very grateful to all field assistants of the Sebitoli Chimpanzee Project who were confined at Sebitoli Station during Covid-19 lockdown, namely, Emmanuel Balinda, Deogratius Kiomuhangi, Joseph Alinaitwe, Ibrahim Nyakana, Wilson Muzahura, Edward Kalyegira, and Sulaiti Tusabe. We offer profound thanks to Daniela Zainabu Birungi, Robert Asimwe, and Robert Nyakahuma for their assistance for the plastic waste collection and to Clovice Alikonyera, Charles Twesige, and Philip Musinguzi for the road patrols. We are grateful to the Fondation Nicolas Hulot pour la Nature et pour l´Homme, the Fondation Prince Albert II, and the Fonds Fran çais pour l´Environnement Mondial for financial support. We deeply thank Kazuhiko Hosaka, Noriko Itoh and William C. McGrew for their valuable comments to improve this manuscript. REFERENCES Bates AE, Primack RB, Moraga P, Duarte CM 2020. COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown as a "Global Human Confinement Experiment" to investigate biodiversity conservation. Biol Conserv 248:108665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108665 Bortolamiol S, Cohen M, Jiguet F et al. 2016. Chimpanzee non-avoidance of hyper-proximity to humans. J Wildl Manag 80:924-934. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.1072 Cibot M, Bortolamiol S, Seguya A, Krief S 2015. Chimpanzees facing a dangerous situation: A high-traffic asphalted road in the Sebitoli area of Kibale National Park, Uganda. Am J Primatol 77:890-900. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22417 Cibot M, Krief S, Philippon J et al. 2016. Feeding consequences of hand and foot disability in wild adult chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). Int J Primatol 37:479-494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-016-9914-0 Krief S, Cibot M, Bortolamiol S et al. 2014. Wild chimpanzees on the edge: Nocturnal activities in croplands. PLoS One 9: e109925. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109925 Krief S, Berny P, Gumisiriza F et al. 2017. Agricultural expansion as risk to endangered wildlife: Pesticide exposure in wild chimpanzees and baboons displaying facial dysplasia. Sci Total Environ 598:647-656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.113 Krief S, Iglesias-Gonzalez A, Appenzeller BMR et al. 2020. Road impact in a protected area with rich biodiversity: The case of the Sebitoli road in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:27914-27925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09098-0 Lindsey P, Allan J, Brehony P et al. 2020. Conserving Africa's wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nat Ecol Evol 4:1300-1310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6 Melin AD, Janiak MC, Marrone II F, Arora PS, Higham J P 2020. Comparative ACE2 variation and primate COVID-19 risk. BioRxiv. (preprint) https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.034967 Rutz C, Loretto MC, Bates AE et al. 2020. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nat Ecol Evol 4:1156-1159. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1237-z Spirhanzlova P, Fini J-B, Demeneix B et al. 2019. Composition and endocrine effects of water collected in the Kibale national park in Uganda. Environ Pollut 251:460-468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.006 Volpato G, Fontefrancesco MF, Gruppuso P, Zocchi DM, Pieroni A 2020. Baby pangolins on my plate: Possible lessons to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 16:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00366-4 Received: 13 August 2020 Accepted: 26 October 2020

Back to Contents |