|

Social Scratch among the Chimpanzees of Gombe

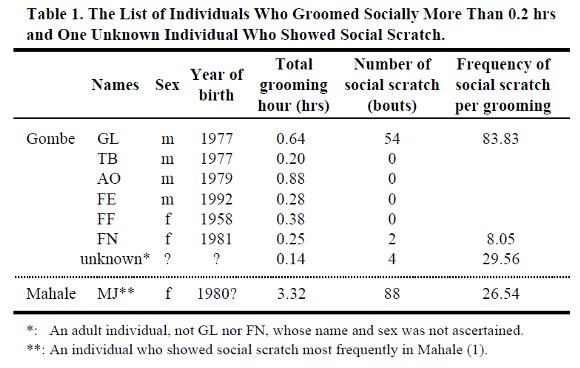

Masaki Shimada Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University Nakamura and others (1) reported that the behavioral pattern of “social scratch” is common among the M group chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania, but it’ s not found among the chimpanzees of Gombe National Park, which is located 150 km north of Mahale, despite more than 40 years of the field work. However, I found some chimpanzees in the Kasakela community of Gombe that scratch socially during my short visit in the park. This paper reports new observations and discusses some features of social scratch in Gombe by comparison with the behavior in Mahale. Observations I visited Gombe and sampled behavioral data of chimpanzees of the Kasakela community (2) from 27 October to 1 November using a digital video camera. My purpose was to compare chimpanzee behaviors between Mahale and Gombe. The Kasakela community included around 50 individuals when I was there (M. Lukasik and E. Greengrass, pers. comm.). I videotaped chimpanzee behaviors by the ad lib. sampling method for 14.1 hrs, during which I recorded grooming for 3.58 hrs as total accumulation of social grooming of each individual. During my observation, field assistants or a researcher identified the individuals for me. A list of names, ages, and family lines of individuals was also made available through the kindness of Dr. S. Kamenya, chief investigator of the Jane Goodall Institute in Gombe. For data analysis, I used the same definition as (1) for a bout of social scratch, in which one bout was defined to be separated from another by other elements of grooming (e.g. stroke or pick). Total grooming hours were calculated by accumulating grooming time in which one individual groomed another. Frequency of social scratch was calculated by dividing the number of social scratch bouts by total grooming hours. Seventeen individuals were observed to groom socially. Table 1 shows the total grooming hours of 6 individuals who groomed for a relatively long time (more than 0.2 hrs). At least 3 individuals (GL, FN, and an unidentified individual) performed social scratch during these observations. Social scratch was observed only when they were grooming another individual. The response of the recipients to social scratch seemed to be “no-reaction”. The frequencies of social scratch per grooming hour by GL and the unknown individual seemed higher than that of the individual who showed the most frequent social scratch in Mahale. I could not determine whether other individuals also performed this behavior due to the short observation time.

Discussion The context and the reaction of the recipients of social scratch in Gombe seemed to be the same as those in Mahale (1). Each of these observations was made only when chimpanzees were grooming socially, and recipients showed no positive reaction to the received social scratch. Nakamura and others (1) argued that most adult individuals in Mahale perform social scratch. All of 6 individuals in Gombe that groomed more than 0.2 hrs were older than 10 years. Two of them (GL and FN) performed social scratch, while the rest of them were not observed to do this. This result suggests that not all of the adult individuals of the Kasakela community in Gombe perform social scratch at this time, while it is thought to be very common among the adult individuals of the M group in Mahale. On the other hand, two performers in Gombe (GL and unknown) seemed to scratch socially more frequently than performers in Mahale (Table 1). The performer who socially scratched most frequently in Mahale was MJ, and the frequency was 26.54 social scratches per grooming hour (1). GL and the unknown’s frequencies of social scratch (83.83 and 29.56, respectively) were higher than even the highest value in Mahale. Although McGrew and Marchant (1) investigated hand laterality of Kasakela chimpanzees from September to December 1992, they never observed social scratch. If no chimpanzee of the Kasakela community performed social scratch or the frequencies were too low to be observed 10 years ago, these three performers (or more) must have somehow acquired the behavioral pattern or their frequencies must have increased significantly over the past 10 years. Two hypotheses can explain the acquisition process (3): 1. The three chimpanzees acquired it independently, thus by individual learning, 2. They acquired it by social learning. Hypothesis 2 can explain this case better than 1, because it is unreasonable to think that they learned their behavior one-by-one independently where the behavior had not existed at all. Some kinds of social learning are thought to promote the propagation of the behavioral pattern in the community. Furthermore, the variation in the social learning may affect the different features of social scratch as discussed above between Gombe and Mahale. If the above hypothesis 2 is the case, the process of social learning and acquisition of the new behavioral pattern are in progress in the Kasakela community, and it is worth studying the concrete process of the phenomenon because cases of social propagation of cultural behavior are very rare in the animal kingdom (4).

In order to answer the question of whether the pattern of social scratch in Gombe and Mahale are the same, we have to investigate how many chimpanzees in the community perform social scratch and what kinds of social learning sustain its propagation. Researchers who are interested in the behavior of social scratch in other fields should study the chimpanzee communities in Gombe.

Back to Contents |