|

<NOTE>

An Annular Solar Eclipse at Mahale: Did Chimpanzees Exhibit Any Response?

Michio Nakamura1 & Hitonaru Nishie1,2

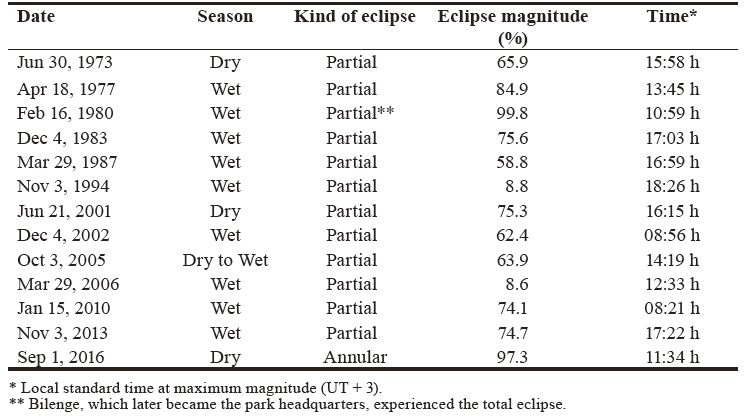

1 Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Japan 2 JSPS Research Fellow INTRODUCTION Contemporary humans often enjoy observing solar eclipses as astronomical shows. In the mystic atmosphere under an eclipsing sun, one might ask, “How ancestral humans faced such events without understanding their causal mechanism? With fear or with fascination?” Similarly, it may be interesting to know how animals respond to such solar events. The behavior of animals in captivity has been observed during solar eclipses. For example, antelope ground squirrels (Ammospermophilus leucurus) exhibit increased locomotor activity during a partial solar eclipse (Kavanau & Rischer 1973). In contrast, hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) become less active during a solar eclipse (Gil-Burmann & Beltrami 2003). Interestingly, captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) have been observed to climb up high structures, orient their bodies toward the sun, and even gesture toward the sun during an annular solar eclipse (Branch & Gust 1986). During an annular eclipse, simultaneous observations of captive chimpanzees were made at eight Japanese institutions (zoos and research institutes). Notable behaviors, such as shouting at the sun, looking up at the sky, or showing general excitement, were reported at four of these institutions (Kato et al. 2013). However, the authors caution that these behaviors may be caused by increased human presence (and excitement) rather than the eclipse itself. There have been fewer reports on the responses of animals in the wild to solar eclipses. In one study, the European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus) did not show any marked behavioral change during a partial eclipse (Spoelstra et al. 2000). An extensive survey on the behaviors of various animals at the Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe during a total eclipse revealed that hippopotamuses and many birds behaved as though it was dusk, impalas exhibited increased vigilance, and baboons exhibited feeding cessation (Murdin 2001). However, there appears to be no reports on the responses of wild chimpanzees to solar eclipses. On September 1, 2016, we unexpectedly observed an annular eclipse at the Kasoje area in the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania, where research on habituated chimpanzees has been conducted for more than 50 years (Nakamura et al. 2015). Although there are no records of solar eclipses at Mahale, online eclipse predictions by Fred Espenak (EclipseWise.com online) indicated that till date, several solar eclipses have occurred in the Kasoje area since the commencement of the chimpanzee study (Table 1). However, this was the first annular eclipse in the Mahale research history (and the next will be in 2064). Therefore, here we report the chimpanzee behavior during this rare annular solar eclipse. Table 1. Solar eclipses observed at Kansyana Camp (6°7′1″S, 29°44′23″E) since the commencement of chimpanzee research in 1965 (based on eclipse predictions by Fred Espenak on EclipseWise.com online).

Particulars of the annular solar eclipse On the day of the eclipse, no author was aware that the event was going to occur. HN was at the Kansyana Research Camp, Kasoje area, at Mahale and was notified of the impending solar event by a research assistant who heard the news on the radio. According to EclipseWise.com (online), the annular eclipse was observed in a wide area from the Indian Ocean to Madagascar and Central Africa to the Atlantic Ocean. At Kansyana (6°7′1″S, 29°44′23″E), the event lasted from 09:49 h to 13:29 h, with the annular state occurring for approximately 2.5 min between 11:32 and 11:35 h at a maximum magnitude of 97.3% (Figure 1).

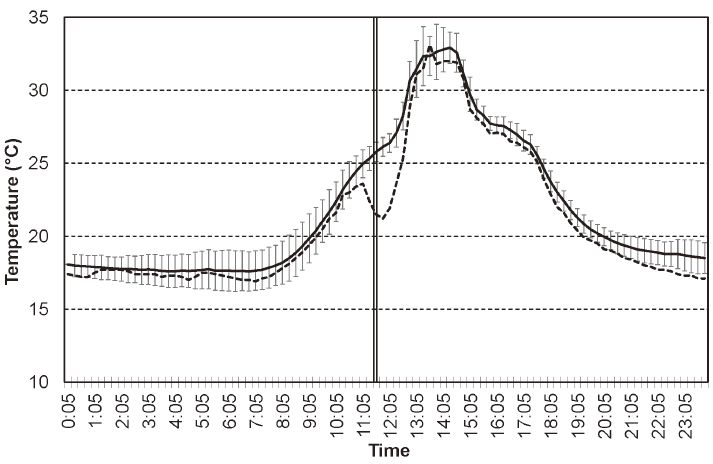

Figure 1. The annular eclipse observed at Kansyana Camp on September 1, 2016. There was no rain during 11 days (August 27 to September 6) including the day of the eclipse owing to September being at the end of the dry season at Mahale. The temperature started falling at 11:00 h, and at 11:50 h, as the eclipse was receding, the temperature was approximately 5°C below the average temperature on the surrounding 10 days (Figure 2); at 12:50 h, toward the end of the eclipse, this difference reduced below 2°C. We did not monitor luminous intensity, but when the eclipse was at maximum magnitude, HN felt that it was as dark as at dusk.

Figure 2. Comparison of temperatures between the day of the eclipse (dashed line) and the average of the surrounding 10-day period (August 27–31 and September 2–6) (solid line). Error bars show standard deviations. A double vertical line shows the time of the annular eclipse. Chimpanzee behavior during the solar eclipse On the day of the eclipse, MN met a party of chimpanzees including the alpha male at 07:55 h and started following an adult female, Linda (estimated to be 36 years old), at 08:28 h. At around 09:30 h, most party members began moving westward, whereas Linda and her 4-year-old daughter, Lenge, did not follow the others and started moving eastward. At around 11:00 h, MN noticed that the sky began to darken. Being unaware of the occurrence of the eclipse and with limited visibility of the sky from the forest, he thought that the sun was being obscured by thick clouds, as it often happens during the wet season at Mahale, and wrote in the field notes: “it is becoming cloudy”; at 11:30 h, he wrote, “it is very gloomy”; and at 11:59 h, he wrote, “sunlight is back.” MN continued to follow Linda until 17:00 h. On return to the research camp, he was informed by HN that the eclipse had occurred. Ex post facto investigation was conducted on the behaviors of the focal female, Linda, and her daughter, Lenge, during the eclipse. At 11:00 h, when MN first noticed that the sky had begun to dim, Linda was feeding on Saba comorensis fruits and Lenge was resting in a nearby bed. Soon, they began moving eastward. At 11:13 h, Linda made some tools, and both chimpanzees began fishing for arboreal ants. At 11:30 h, when the sky was the darkest, they were still fishing for ants. Linda continued fishing for ants (Figure 3) until 14:56 h, whereas Lenge fished intermittently, begged Linda for tools or a place to fish ants, suckled on Linda’s nipple, or foraged nearby for fruits. There was no indication that Linda or Lenge particularly changed their behavior during the eclipse. Although the two were by themselves when the eclipse occurred, MN was aware that other chimpanzees were nearby, so calls by other chimpanzees would have been heard. As no calls were heard during the time of the eclipse, it was assumed that the other chimpanzees did not vocally respond to the eclipse.

Figure 3. Linda (above) and Lenge (below) fishing for ants at 12:48 h on the day of the eclipse. DISCUSSION Unlike that in previous studies on captive chimpanzees (e.g., Branch & Gust 1986), Linda and her daughter, Lenge, did not exhibit any specific behavioral change during the eclipse, and continued fishing for ants in the tree. This lack of response to the eclipse may have been due to them not being able to see the eclipsing sun as the location where they were fishing for ants was covered by a thick canopy of leaves. This may be consistent with the results in the report on captive chimpanzees, in which cloud cover prevented the observation of the eclipse because of which chimpanzees exhibited no any specific response (Kato et al. 2013). Apparent excitement or curiosity observed in some captive chimpanzees may be more likely when there is no overhead coverage, as in zoos, and when the eclipsing sun is directly visible. Owing to overhead tree coverage, wild chimpanzees may not be able to directly observe eclipse events. Thus the question is whether or not wild chimpanzees can detect something unusual in the unexpected onset of darkness alone. As we experienced an annular rather than a total solar eclipse in the present study, although it became quite dark, it still was sufficiently bright for chimpanzees to continue ant-fishing and for MN to write field notes. During partial eclipses with smaller eclipse magnitudes, it may be increasingly difficult for chimpanzees to detect a difference between darkness caused by cloudiness and that by eclipse. Onset of darkness to some extent may not affect them much as they are accustomed to such darkening events by sudden occurrences of heavy clouds in the wet season. Furthermore, it is likely that solar eclipses during the wet season go unnoticed because the sky is often covered with thick clouds. This may also explain the lack of previous reports on eclipses at Mahale, as most eclipses occurred in the wet season (Table 1). Although wild chimpanzees are known to perform “rain dances” when it starts raining heavily (Goodall 1986), no obvious behavioral changes have been noted when the sun is simply obscured by thick clouds. Thus, the lack of obvious behavioral changes by Linda and Lenge was unsurprising. The question still remains on how chimpanzees respond during a total solar eclipse when the forest is suddenly covered in complete darkness during the day. There will be long wait before a total eclipse occurs at Mahale or at other chimpanzee research sites in the wild. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank COSTECH, TAWIRI, and TANAPA for permission to conduct research at Mahale. HN’s field study was financially supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (#14J00963). REFERENCES Branch JE, Gust DA 1986. Effect of solar eclipse on the behavior of a captive group of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am J Primatol 11:367–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.1350110407 EclipseWise.com [online] Available at: http://eclipsewise.com/. [Accessed November 29, 2016]. Gil-Burmann C, Beltrami M 2003. Effect of solar eclipse on the behavior of a captive group of hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas). Zoo Biol 22:299–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.10077 Goodall J 1986. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Belknap Press, Cambridge, Mass. Kato Y, Yamada N, Konishi K et al. 2013. [Behaviors of captive chimpanzees at annular solar eclipse: Comparisons of eight Japanese zoos and institutes by application of a mailing list.] Internet J Environ Enrichment 7:e142, in Japanese. Kavanau JL, Rischer CE 1973. Ground squirrel behaviour during a partial solar eclipse. Bolletino Zool 40:217–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/11250007309430071 Murdin P 2001. Effects of the 2001 total solar eclipse on African wildlife. Astron Geophys 42:40–42. Nakamura M, Hosaka K, Itoh N, Zamma K (eds) 2015. Mahale Chimpanzees: 50 Years of Research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107280533 Spoelstra K, Strijkstra AM, Daan S 2000. Ground squirrel activity during the solar eclipse of August 11, 1999. Z Saugetierkunde 65:307–308. Back to Contents |