|

<NOTE>

Discriminating Saba and Landolphia Seeds in Chimpanzee Feces at Mahale

Michio Nakamura

Wildlife Research Center, Kyoto University, Japan INTRODUCTION The fruits of Saba comorensis (local name, ilombo) and Landolphia owariensis (local name, mpila) are often enthusiastically eaten by chimpanzees at Mahale, and they have been classified as a “major food” and “important food,” respectively, by Nishida (1991). Both of them belong to the family Apocynaceae with liana life forms, and they share some common characteristics. However, the fruits of Saba and Landolphia are easily distinguishable by their color and size: the ripe fruit-shell color of Saba is yellow, while that of Landolphia is orange; the color of the fruit pulp is yellow in the former and white in the latter, and the fruit size of the former (typically ca. 7–10 cm in fruit-shell diameter) is about twice as large as that of the latter (ca. 3.5–5 cm). Therefore, no researchers would confuse these species when they actually observe chimpanzees eating these fruits. However, it is very difficult to identify the seeds found in chimpanzee feces (see McGrew et al. 2009 for the standard protocol for fecal analysis). Chimpanzees typically swallow seeds of both species together with the fruit pulp. Seeds are then defecated intact in their feces. The shapes and colors of their seeds resemble each other and are thus not easily distinguishable (Figure 1). Because these fruits are available in the same season, it is also not possible to discriminate them by season. Therefore, Saba and Landolphia were clumped together in most previous studies on seed dispersal and fecal analyses at Mahale (Nishida & Norikoshi n.d.1, n.d.2; Takasaki 1983; Takasaki & Uehara 1984). However, because Saba is the most important fruit species for Mahale chimpanzees, it may be useful to develop some simple criteria to distinguish its seeds from those of Landolphia. The Saba-Landolphia problem in fecal analyses may go beyond Mahale, because different species of these two genera are known to coexist in some other chimpanzee study sites (e.g., Saba senegalensis and Landolphia heudelotii are eaten by Assirik chimpanzees in Senegal: McGrew et al. 1988).

Figure 1. Seeds of Saba (above) and Landolphia (below). Although the former is slightly larger than the latter, it is not easy to distinguish between the seeds in chimpanzee feces. METHODS I collected 25 Saba seeds and 28 Landolphia seeds from ripe fruits (five to six fruits each) of these plants in December 2013 at the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. The fruits were collected from the middle of the home range of the habituated M group. The sampling was performed opportunistically because of the difficulty in randomly collecting fruits from the high canopy where these fruits are typically seen. After removing the fruit pulp and air-drying the seeds, I measured the longest axis (hereafter “length”) and the second longest axis (orthographical to the longest axis, hereafter “width”) of each seeds by using a vernier caliper to the nearest 0.05 mm. Linear discriminant analyses were then conducted using R software (version 2.12.1) with these length and width measures.

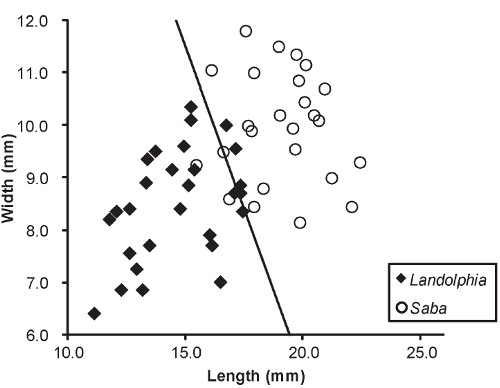

A Mahale chimpanzee feeding on a Saba fruit. I also collected 24 Saba/Landolphia-shaped seeds from a chimpanzee fecal clump found during the same study period. After washing and air-drying, their length and width were measured in the same way. The size data for these seeds were used in order to trial-run the applicability of the analysis. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The length and width data for known Saba and Landolphia seeds are plotted in Figure 2. Saba seeds averaged 19.06 (± 1.81 SD) mm in length and 9.97 (± 1.05) mm in width, while Landolphia seeds averaged 14.64 (± 1.92) mm by 8.49 (± 1.05) mm. Saba tends to have a longer and wider shape than Landolphia, but there is still some overlap in their sizes. It seems that length has less overlap than width (thus, Saba is relatively longer and ovoid than Landolphia).

Linear discriminant analysis yielded the discriminating function of the two species (Dsp) in the following formula:

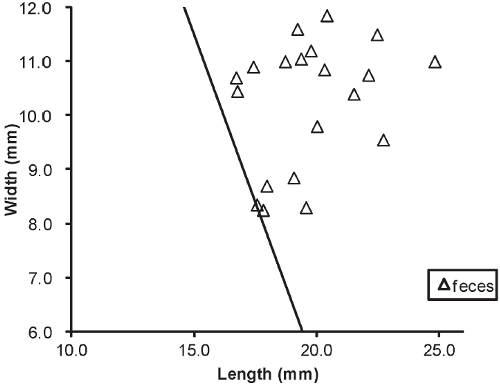

Figure 2. Length-width plots of known Saba and Landolphia seeds. The line is the discrimination line between the two species (i.e., Dsp = 0). Although a few seeds of each species are inaccurately judged as the other, 88.68% of the data points are plotted on the correct sides of the line. When length/width values of the 24 unidentified Saba/Landolphia-shaped seeds from a chimpanzee fecal clump were assigned to this formula, all but one was judged as Saba (Figure 3). I assume that the fecal clump actually contained only Saba seeds (i.e., one was misjudged as Landolphia) for the following reasons. First, the one judged as Landolphia was almost on the border of these two species (Dsp = 0.002), and the proportion of seeds judged as Saba (95.83% = 23/24) was higher than the discrimination accuracy of 88.68% (thus, it is very likely that a small portion was misjudged). Second, because chimpanzees usually swallow multiple seeds of a Saba/Landolphia fruit at a time, that is, a fecal clump is expected to contain multiple seeds from one fruit, it is not very likely (though not completely impossible) that only one Landolphia seed was contained in a fecal clump with many Saba seeds. In addition, direct observations of feeding at the time showed that the chimpanzees more often fed on Saba than Landolphia.

Figure 3. Length-width plots of unknown Saba/Landolphia-shaped seeds from chimpanzee feces. The line is the same discrimination line (i.e., Dsp = 0) as that in Figure 2. Almost all seeds are plotted on the side of Saba. Although this result is preliminary and we may need more data by performing additional random sampling of fruits, simple measurements of the length and width of a seed seem to distinguish these two species with an accuracy of close to 90%. There are, of course, more accurate ways to discriminate the species, for example, by germination tests to confirm the species by the characteristics of their seedlings or by DNA analyses to genetically identify species. However, measuring sizes is far easier for field researchers. Thus, this may be useful for future studies of chimpanzee seed dispersal and/or fecal analyses at and around Mahale, especially on unhabituated chimpanzee groups whose direct observation is often difficult but who may share similar food items with the M group. A similar method may also be applicable to other study sites where Saba-Landolphia (and other confusing sets of species or genera) coexist, with modifications of the formula with their own data sets. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank COSTECH, TAWIRI, and TANAPA for their permission to conduct long-term research at Mahale. I would also like to thank Dr. William C. McGrew for useful suggestions on the manuscript. This study was financially supported by the Toyota Foundation. REFERENCES McGrew WC, Baldwin PJ, Tutin CEG 1988. Diet of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) at Mt. Assirik, Senegal: I. Composition. Am J Primatol 16:213–226. McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Phillips CA 2009. Standardised protocol for primate faecal analysis. Primates 590:363–366. Nishida T 1991. Primate gastronomy: cultural food preferences in nonhuman primate and origins of cuisine. In: Chemical Senses. Vol. 4. Appetite and Nutrition, Friedman MI, Tordoff MG, Kare MR (eds), Marcel Dekker, Inc, New York, pp. 195–209. Nishida T, Norikoshi K n.d.1. The study of food on a basis of fecal analysis of the chimpanzees of the K-group and the M-group, June–November, 1975. Mahale Mountains Chimpanzee Research Project Ecological Report 1 (unpublished report). Nishida T, Norikoshi K n.d.2. The study of food on fecal analysis of the chimpanzees of the K-group and the M-group, December 1975–May 1976. Mahale Mountains Chimpanzee Research Project Ecological Report 2 (unpublished report). Takasaki H 1983. Seed dispersal by chimpanzees: a preliminary note. Afr Stud Monogr 3:105–108. Takasaki H, Uehara S 1984. Seed dispersal by chimpanzees: supplementary note 1. Afr Stud Monogr 5:91–92. Back to Contents |