|

<NOTE>

Comparison of the Longevity of Chimpanzee Beds between Two Areas in the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania

Koichiro Zamma1,2 & Masayuke Makelele2

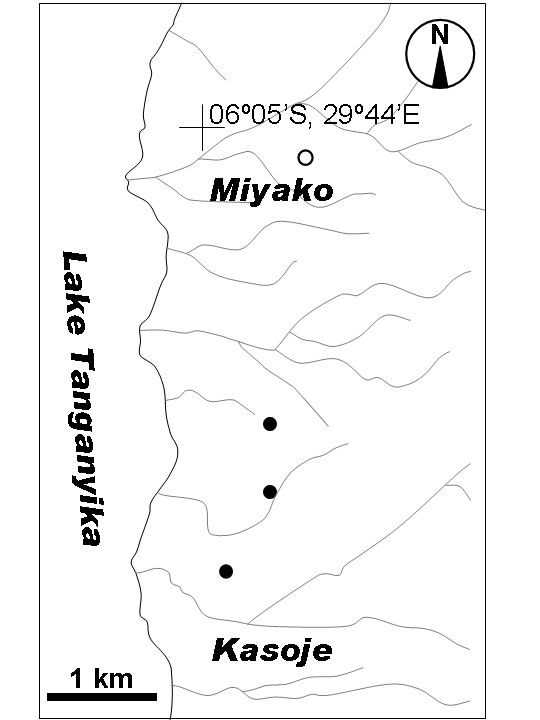

1 Great Ape Research Institute, Hayashibara, Japan 2 Mahale Mountains Chimpanzee Research Project INTRODUCTION Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) beds have been used as an indicator for the presence of chimpanzees, and the longevity of beds is one of the important variables for estimating chimpanzee population sizes1,2. The longevity of chimpanzee beds can differ due to location, vegetation, and season3–6. For example, beds in forested sites decay faster than those in woodlands5, and beds in the dry season decay faster than those in the rainy season3,5. A previous study6 on the longevity of chimpanzee beds was conducted in the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. Because the study6 was conducted only in the forested area in the dry season, we studied chimpanzee beds both in forested and woodland sites during the rainy season. METHODS This study was conducted in Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. This site has a rainy season from early October to mid-May7. We focused our research in two areas in the park, Kasoje and Miyako (Figure 1). The Kasoje area is composed of gallery forest8,9, and is the center of the range of the M group of chimpanzees. The Miyako area consists of Brachystegia woodland with gallery forest along riverside area8,9, and is occupied by chimpanzees of the Y group10.

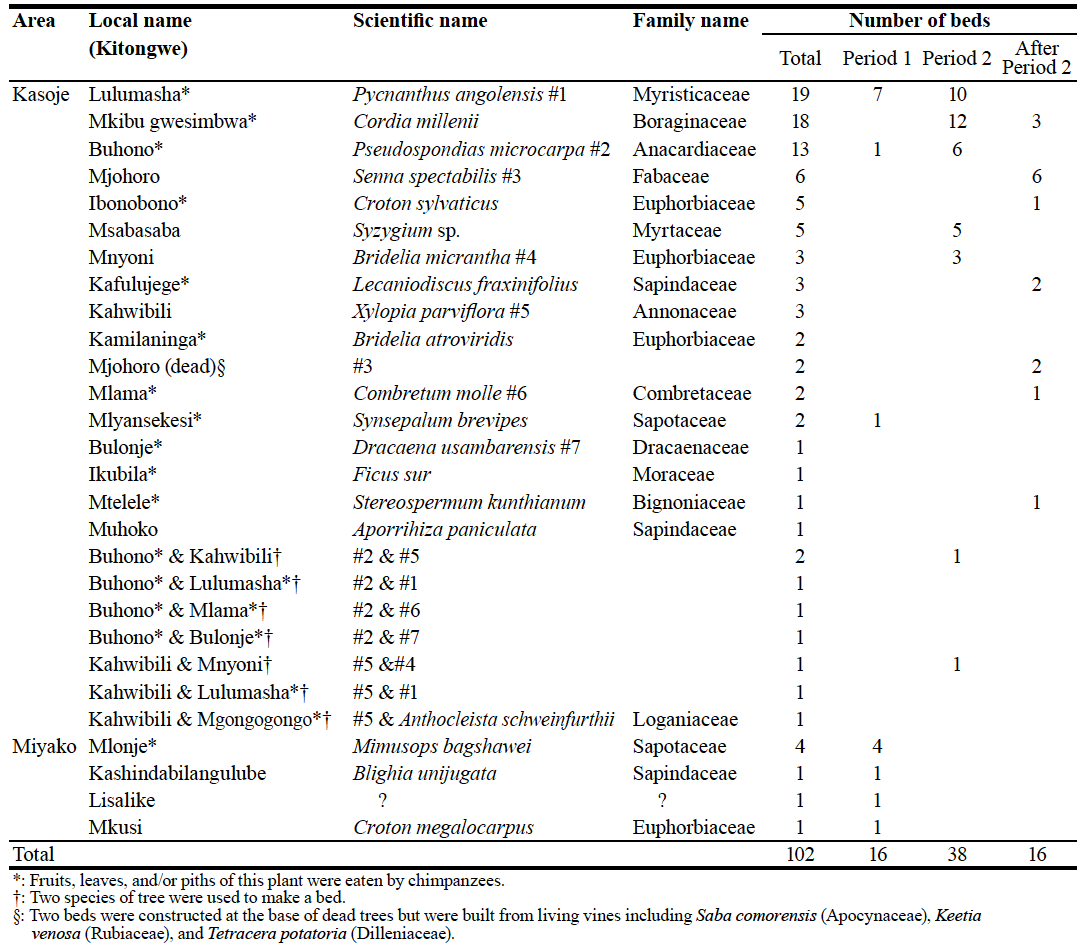

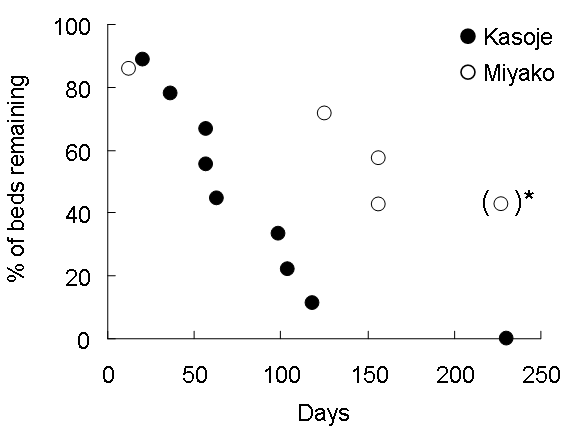

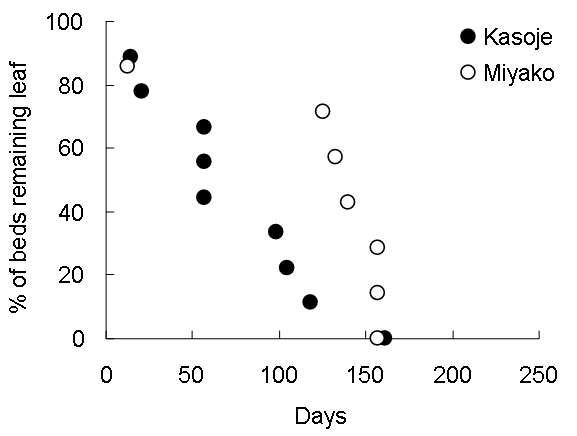

Figure 1. Locations of chimpanzee beds in Kasoje (closed circle) and Miyako (open circle) during period 1. Across both sites, we found 102 fresh beds from 3 October 2006 to 16 February 2007, and classified them by their date of construction (Table 1). Of these, we selected 70 beds to estimate bed longevity, and 32 beds to study bed construction. For the longevity study, we classified beds into two categories based on their time of construction. Beds constructed during Period 1 (3 to 10 October) were monitored until 24 May 2007. Beds constructed during Period 2 (11 October to 10 November) were monitored for a minimum of 100 days. Beds constructed after Period 2 were not included in analyses. Table 1. Tree species used for chimpanzee bed. Beds were monitored approximately once per week (mean interval = 8.7 days, range = 6–28 days). KZ monitored the beds from 3 October 2006 to 16 February 2007, and MM monitored them from 17 February to 24 May 2007. We defined bed leaves as decayed when all of leaves had fallen from the branches in the bed3,5, and defined beds as decayed when they were no longer clearly discernable as chimpanzee beds1,2,4–6. We monitored 9 beds in the Kasoje area and 7 beds in the Miyako area during Period 1. During Period 2, we monitored 38 beds in Kasoje area. The minimum distance between bed sites of the two areas was about 2 km (Figure 1). RESULTS We recorded 21 tree species that were used for constructing chimpanzee beds (Table 1). The most frequently used species was Pycnanthus angolensis, followed by Cordia millenii and Pseudospondias microcarpa. Many of the trees in which beds were constructed (78/102) are known food trees of Mahale chimpanzees. Eight beds were also found in the invasive tree, Senna spectabilis, and two of them were constructed at the base of dead trees. The mean longevity of chimpanzee beds during Period 1 was 87 days (n = 9, range = 21–231) in the Kasoje area and 164 days (n = 7, range = 13 to > 233) in the Miyako area (Figure 2). Three beds in the Miyako area were not decayed by the end of the survey period. Bed longevity was significantly longer in Miyako than in Kasoje (Mann-Whitney U test, n1 = 9, n2 = 7, U = 12, p < 0.05).

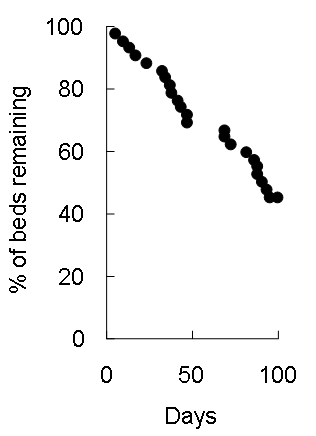

Figure 2. Rate of decay of chimpanzee beds in period 1. *: Three beds were remained undecayed. During Period 2, we monitored 38 chimpanzee beds in Kasoje. We set a 100 day limit for monitoring these beds and more than half of the beds (22/38) were decayed by the end of this period (Figure 3). This was not statistically different from the decay rate for Period 1 beds in Kasoje over 100 days (6/9; Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.72), but was significantly greater than the decay rate for beds in Miyako (1/7; Fisher’s exact test p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Rate of decay of chimpanzee beds in Kasoje in Period 2. The mean time for leaf decomposition in beds was 76 days in Kasoje (n = 9, range = 14–158) and 126 days in Miyako (n = 7, range = 13–157). These numbers were not statistically different according to a Mann-Whitney U test (Figure 4, n1 = 9, n2 = 7, U = 15, p = 0.088).

Figure 4. Rate of decay of bed leaves in Period 1. DISCUSSION There are two methods for measuring the longevity of chimpanzee beds: the time until leaves decays and the time until the bed structure decays1–6. Bed leaves decayed faster in Kasoje in the dry season (49 days, n = 41, range = 18–110)6 than in the rainy season (76 days) in this study. In tree species of bed no remarkable differences could be seen between this and previous study, and Pycnanthus angolensis was the most frequently used species in both studies. Leaves in the dry season are thought to have lower moisture content and, thus, decay faster3. The result in this study is consistent with previous studies3,5. In contrast, the longevity of bed structures in Kasoje was longer in the dry season (131 days, n = 41, range = 30–189)6 than in the rainy season (87 days) in this study. This indicates that different mechanisms are relevant for the decay of leaves in beds than for decay of the bed structure. Over the period of this study (3 October 2006 –24 May 2007) 1,562 mm of precipitation fell and almost two-thirds of the total precipitation (1,001 mm) fell during the first 3 months (Mahale Mountains Chimpanzee Research Project data). We propose a hypothesis: because dead leaves often remain in branch structure in beds and absorb rainfall during the rainy season, the increased weight of the wet branches may contribute to the deterioration of the bed structure. The longevity of chimpanzee beds in Miyako was longer than that in Kasoje, but this difference cannot be explained by rainfall because the amount of precipitation did not differ between the two areas11. The longevity of chimpanzee beds in woodlands in the Ugalla area, Tanzania is long (more than 358 days (Yoshikawa M, personal communication); 432 days5), and beds in Miyako area also constructed in woodland. The strength of branches of tree species in woodland may be a key factor contributing to the longevity of chimpanzee beds in these areas. The present study and previous studies (e.g. ref. 1–6) indicate that the longevity of chimpanzee beds differs according to season and vegetation type. These studies indicate the need for broader range of bed longevity or for appropriate estimates of bed longevity in each site to accurately estimate chimpanzee population sizes. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank TAWIRI, TANAPA and COSTECH for permission to do the field research, and MMNP and MMWRC for logistic support. We also thank T. Sakamaki for providing information about the beds of Y group chimpanzees, H. Bunengwa, M. Mwami, H. Ihobe, N. Itoh, H. Ogawa, and M. Yoshikawa for their help and advices, the members of MMCRP for providing precipitation data, and M. Kiyono and C. Tokimatsu for data handling. This study was financially supported by the Global Environment Research Fund of the Ministry of Environment, Japan (F-061 to T. Nishida). REFERENCES

Back to Contents |