|

Increased hunting of yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) by M group chimpanzees at Mahale.

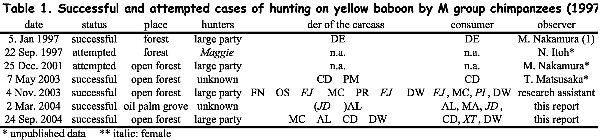

Kyoto University Introduction Since the first observation by Nakamura1, no one has reported cases of predation on yellow baboons by the M group chimpanzees at Mahale. Nishida2, 3 reported that some baboon groups had invaded the range of the M group chimpanzees from the early 1990s, and direct encounters between chimpanzees and baboons have been observed (N. Itoh, T. Matsusaka, M. Nakamura, K. Zamma & T. Nishida, unpublished). Furthermore, many authors3, 4, 5 have reported the importance of indirect competition between baboons and chimpanzees. However, it is still unclear how possible competition influences the relationship between them.

There have been no reports of predation on baboons by chimpanzees at other sites, aside from Gombe where olive baboons (Papio anubis) were formerly preyed upon by chimpanzees6. This variation in prey selection among chimpanzee populations may be explained partly by differences in ecological factors and partly by local traditions6. At 9:38, Alofu, holding the carcass, allowed Masudi to bite off some meat from it. At 9:45, Masudi approached again, but this time turned his back on Masudi. Jidda stayed lower, picking up some bone pieces and sucking on them. At 9:57, Masudi approached Alofu again, and this time Alofu let him bite the meat. At 10:01, Masudi tore a leg of the prey off and moved away. Then both males continued to eat the meat. At 10:21, Jidda climbed to the ground and sought out bone pieces. At 10:24, Masudi came down. Masudi had already consumed a whole leg. Alofu followed Masudi and sometimes stopped to eat the meat.

At 10:34, Alofu resumed eating the meat, while Masudi and Jidda moved on. At 10:46, Alofu left and caught up with Masudi and Jidda, later stopping to eat the meat. At 10:50, the three chimpanzees moved into a swamp, ending my observation. At 10:55, Alofu was seen no longer carrying the meat. Therefore, I could not confirm whether Alofu had consumed the meat entirely or abandoned it.

At 8:25, Michio (juvenile male) on a tree near the activity grasped a juvenile yellow baboon and released it at once, and then Alofu immediately captured it (Figure 1). Alofu came down from a tree and dragged the prey on the ground. Alofu sometimes let the prey run away and soon recaptured it. The prey, bleeding slightly from the abdomen, was still alive. There were at least 15 chimpanzees in the area; some followed Alofu, others just stared at him.

Figure 1. Alofu caputuring a juvenile baboon.

At 8:37, Alofu abandoned the prey without killing it. Then Cadmus (young male) captured it and climbed a tree. At 8:39, Cadmus swung the prey and hit it against a branch, which appeared to kill it. At 8:42, Cadmus returned to the ground and slapped and stamped the prey. At 8:44, Cadmus climbed up a tree. Then Orion (young male) came and stared at Cadmus. At 8:46, Michio climbed the tree and approached Cadmus. Cadmus began eating the baboon. At 8:50, Orion moved away. At 8:55, Cadmus swung the prey and dropped it on the ground. Michio approached to pick it up but was charged by Cadmus. Cadmus climbed the tree and resumed eating the meat. At 9:05, Darwin (young male) climbed up the tree to approach Cadmus. Darwin began to perform pant-hoot. Then, Darwin began to whimper and scream near Cadmus, who was eating the meat.

At 9:44, Cadmus dropped the carcass, and Darwin picked it up. Cadmus climbed down and left. Only the area around the prey's head was consumed. At 9:50, Christina (adult female) arrived with her daughter and mated with Darwin. At 9:55, Xtina picked up a bone piece and left. At 9:59, Darwin dragged the carcass. At 10:07, Darwin resumed eating the prey's legs and arms in a tree. At 10:45, Darwin released the carcass and began eating fruit. At 10:48, Darwin swung the carcass and dropped it. Darwin came down to pick it up. At 10:50, Darwin abandoned the carcass and moved away. The carcass had been consumed around the head, part of the abdomen, some parts of the arms, and both legs. In Case 1, all attendants (Alofu, Masudi, and Jidda) seemed eager to get the meat of the infant baboon. Alofu, the holder, kept the prey for a long time and was reluctant to share the meat with Masudi. This indicates that at least the chimpanzees of the M group sometimes have the desire to eat the meat of baboons. In Case 2, however, the first holder, Alofu, released the juvenile baboon without killing it. Moreover, although more than 15 chimpanzees were present, just a few begged for the meat, and these did not persist for long. The other holders, Cadmus and Darwin, also ate just a little of the meat and eventually left much of it uneaten. What accounts for this difference? It is likely that the size of the prey influenced the attitude of the chimpanzees. In the case of hunting red colobus, the main prey of the M group, chimpanzees also show a preference for small prey rather than larger prey. The prey size of Case 2 was slightly larger than that of Case 1 and thus, perhaps, less attractive.

Moreover, the variation in chimpanzee attitudes toward baboons might indicate the flexibility of the behavior, which has not yet become customary among the group's members. It is important to collect variations in behavioral repertoires among chimpanzee populations to characterize chimpanzee cultures; however, gathering detailed descriptions of diachronic changes in behaviors within a chimpanzee unit-group is even more important for understanding how chimpanzees experience their own "familiar" and "usual" world.

Back to Contents |